By Elliott Bledsoe, Co-lead

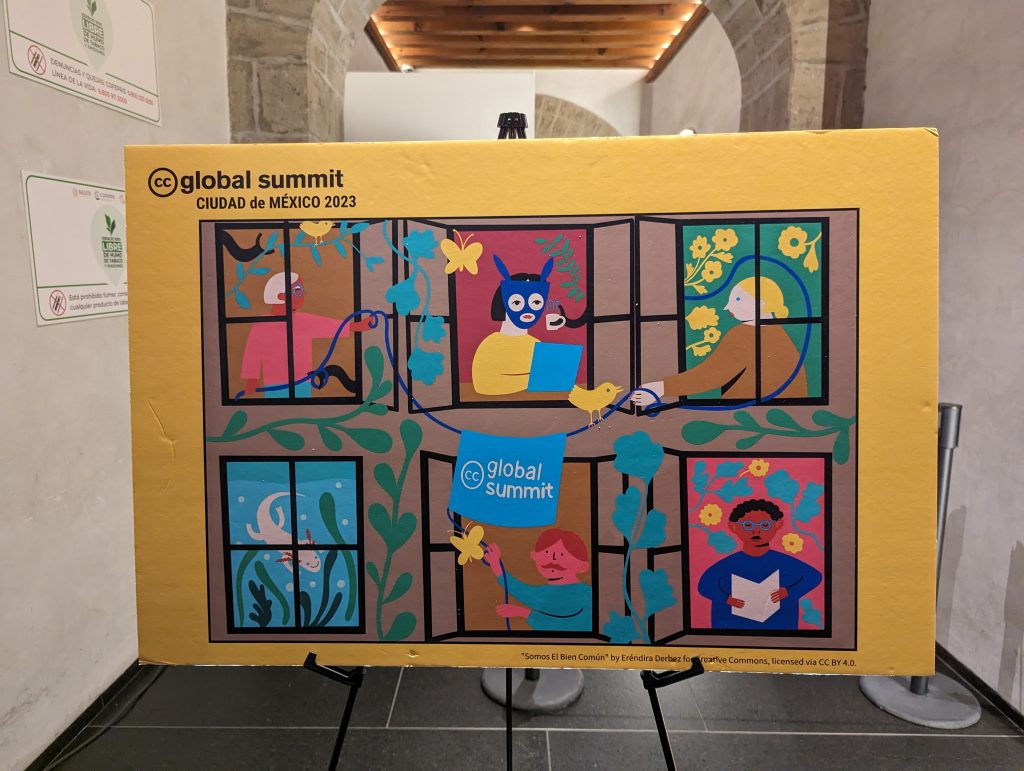

It is hard to believe that it is almost a month since the Creative Commons Global Summit took place at the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco in Mexico City. It was amazing to gather and (re)connect with the creators, advocates, librarians, educators, lawyers, and technologists that engage with CC. I am thankful to the Australian Digital Alliance for the support to attend the Summit.

This year’s Summit was themed ‘AI & the Commons’, exploring the opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence (AI) for access to knowledge and culture. What struck me most was how important open knowledge and culture is, now more than ever. As we continue to move towards a world where large volumes of information (and the technology around it) is increasingly controlled by a few powerful companies, it is essential that open knowledge and culture movements advocate and agitate for a more open and equitable future through collaboration and collective action.

What struck me most was how important open knowledge and culture is, now more than ever.

The copyright issues around AI have been hotly debated in the past 12 months, both here in Australia and around the world. Copyright is just one of the issues that arise in relation to AI. The conversation at the CC Summit delved into complex inequalities inherent in AI. How AI compounds representation bias was raised by karen darricades, Head of Arts and Culture at Creative Commons Canada, who cautioned us that AI trained on the ‘free internet’ results in a transference of existing gaps in representation in visual and textual communication. AI also doesn’t understand race or gender, only what is available in the datasets it’s trained on. To address this we are seeing a ‘synthetic diversity’ built into systems.

Like other internet-based technologies, digital literacy and the digital divide apply to the uptake and development of AI. Patricia Diaz, who is the coordinator of Laboratorio de datos y sociedad (Data and Society Laboratory) and a founder of Creative Commons Uruguay, noted that some regions such as Latin America are lagging behind in the use and development of AI. Many of these regions also do not have copyright exceptions conducive to the development of AI. Because exceptions for AI are less common in the global south, the global north enjoys a significant advantage. Relatedly, Matías Butelman, Co-founder of Bibliohack and Lead of Creative Commons Argentina, added that there are previous conditions that need to be met in order to achieve ‘open’. Countries are at different points on that journey. Additionally, we need to be mindful of the potential for AI to create new forms of inequality and exclusion.

Of course, ethics and AI is a big topic, and a multifaceted one. James Grimmelmann, the Tessler Family Professor of Digital and Information Law at Cornell Tech and Cornell Law School, noted there are lots of players, participants and stakeholders impacted by AI so a ‘one size fits all’ solution isn’t possible. Issues are tied to a lack of transparency around AI systems and proprietary ownership of those systems, for example. Both are at odds with ‘openness’. As Francisco J. Rivas Mesa (Tito Rivas) said, the open community cannot allow technology to be led by companies whose motivations or interests are unknown.

Unauthorised use of copyright material as AI training data is behind a lot of backlash from creators. Teresa Nobre, Legal Director at Communia, commented that currently creators are not being given agency in relation to AI, such as the ability to opt out, and regulatory mechanisms are not yet in place. Protecting creators is an important endeavour for sure, but I am interested how such moves can be reconciled with the impracticalities of copyright licensing for AI projects and the application of exceptions for AI (in territories where a broad fair use-style exception or a specific text and data mining exception exists).

Another issue that was raised many times was to whom authorship and ownership of AI outputs should be ascribed, if anyone at all. I feel it is too early to say where we will land on this topic, and international consensus is unlikely. Perhaps more important is the question of what copyright ownership of AI-generated information means for access to knowledge. My recent appointment to the Management Committee of Wikimedia Australia has left me thinking a lot about what Wikipedia means in a world where the majority of new knowledge is generated by machines – and potentially owned by the machine’s maker or operator.

The AI conversation at the Summit was not all doom and gloom though. AI was also seen as a powerful tool for open knowledge and culture. Artist Empress Trash (Drea Jay) talked about how she has incorporated AI into her creative practice and urged attendees to stop trying to work out how old paradigms interact with AI and just give it some space. Tito Rivas, Peter-Lucas Jones, CEO of Te Hiku Media, and other speakers also pointed to ways AI supports collection management, such as categorisation, cataloguing and translation, increasing administrative efficiency and creating new knowledge. This rang true in Anya Kamenetz’s comment that we should let ChatGPT do all the boring stuff so we can do more of the fun stuff.

…stop trying to work out how old paradigms interact with AI and just give it some space

Empress Trash (Drea Jay)

More on the policy end, both Catherine Stihler, CEO of Creative Commons, and Kat Walsh, CC’s General Counsel, noted parts of the open community have been looking to CC for guidance on AI, particularly how to respond to unethical practices. New coalitions, strategies and tools are needed to ensure AI is ethical and for the benefit of all, and copyright is not the only tool that can be used to respond to AI – a point that was made by Nick Garcia, Policy Counsel at Public Knowledge.

Further, Garcia noted that issues with AI cross many topics that are important to open knowledge and culture movements, not just access to knowledge and copyright and IP. It impacts cultural participation, freedom of expression, platform governance, social justice, equity and inclusion, respect for Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) and other topics. These connection points create room for those new coalitions, strategies and tools to emerge dynamically and organically.

In many ways the challenges AI presents coincide with a shift in how CC and the open community thinks about their goals. Perhaps serendipitously for CC, for example, there has been a shift from a copyright-centred approach to ‘open up’ culture to a more nuanced idea that sharing of knowledge and culture must be contextual, inclusive, just, equitable, reciprocal and sustainable. This sentiment was also expressed by Maja Drabczyk, Head of Policy and Advocacy, Centrum Cyfrowe and Alek Tarkowski, Director of Strategy, Open Future who shared findings from interviews with digital activists and open movement leaders that signalled a shift to what they call a ‘post-copyright approach to openness’. CC’s strategy seeking to create a brighter future through better, more ethical sharing is coupled with the notion that access to knowledge and culture is necessary to solve the world’s greatest challenges.

Conceptually, ethical sharing can accommodate the broad goals of open knowledge and culture movements to enable access to knowledge, while recognising and respecting that there are contexts where unencumbered openness is not appropriate – a point made by Lila Bailey, Senior Policy Counsel at Internet Archive during the Summit. The use of ICIP in AI projects (or any other use for that matter) is a particular case in point. This was articulately taken up by Peter-Lucas Jones, who reminded us that cultural context when working with Indigenous languages is important, because without it language can be misconstrued. Indigenous responsibility to their ICIP necessitates the ability to control who can access knowledge.

Ethical sharing can accommodate the broad goals of open knowledge and culture movements … while recognising and respecting that there are contexts where unencumbered openness is not appropriate

Linking open movements with civil society, social justice, equity, sustainability, and similar pursuits highlights points of solidarity that can be actioned collectively. We have already seen this play out in collaborative initiatives such as the Open COVID Pledge and the Open Climate Campaign. Another collaborative initiative being led by CC that was discussed at the Summit was Towards a Recommendation on Open Culture (TAROC). TAROC seeks to see the establishment of a UNESCO recommendation on Open Culture in a similar vein to the Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER) and Recommendation on Open Science. TAROC connects cultural policy with other policy areas such as innovation, cultural participation and digital rights.

Importantly, to fully realise an Open Culture Recommendation, it must be recognised that galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAM) and other cultural, educational and scientific bodies are important players in developing a thriving knowledge and cultural commons. But more work needs to be done to encourage and support these institutions to enable access to their collections for sharing and reuse.

A final topic that came up at the Summit I feel warrants commenting on is custodianship of the CC licences and other legal tools. Creative Commons was founded 20 years ago and the ways in which the licences are used has diversified over time. The shape and scope of the open community has changed as well. While CC’s purpose has evolved in response, what hasn’t changed is CC’s commitment to stewarding its legal tools, keeping them fit for purpose. For example, currently CC is consulting about a proposal to combine CC0 and the Public Domain Mark.

This is just a handful of the insights that came out of this year’s CC Summit. There were so many more important points raised by speakers and audiences alike. Needless to say, attending was worthwhile, and I am excited to continue sharing those insights with the CC Australia community.

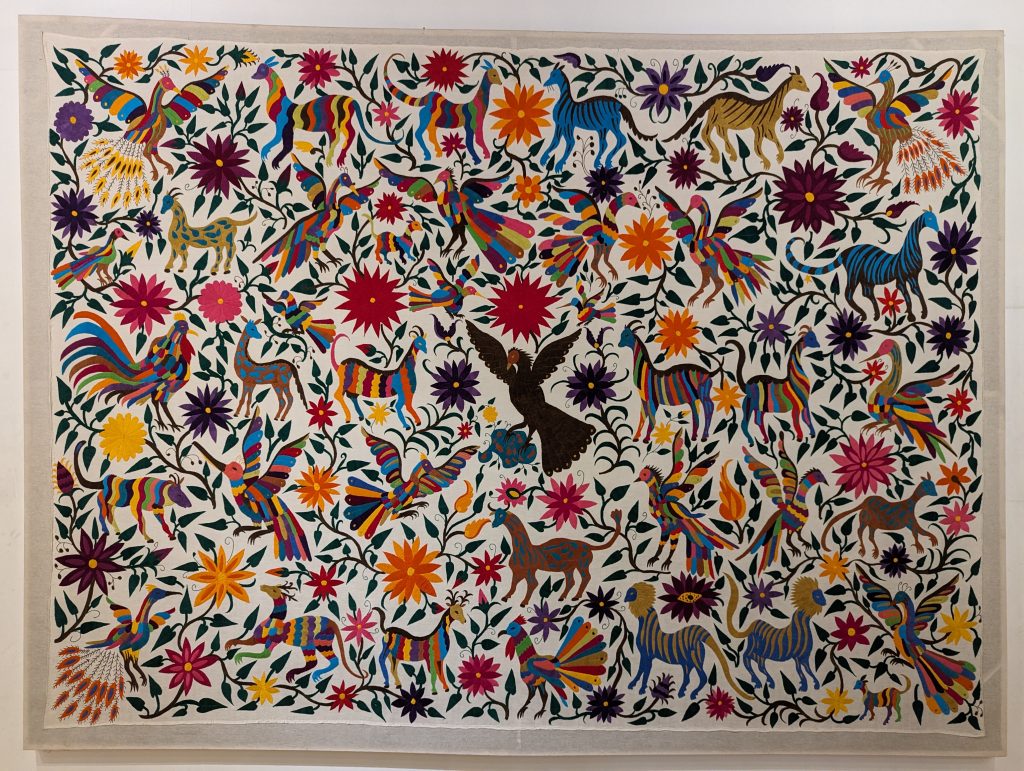

On a personal level, I was very privileged to have the opportunity to immerse myself in Mexican culture while I was in Mexico City. It was thrilling to see so much rich and colourful cultural content through the many galleries and museums I visited and the many street tacos I got to eat!

Colourful embroidery by María de los Ángeles Licona San Juan. Displayed at Museo Indígena (Indigenous Museum), Mexico City. Part of the Colección Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (National Institute of Indigenous Peoples Collection).

A beautiful and colourful example of an árbol de la vida (tree of life) Mexican pottery sculpture in the courtyard at Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares (National Museum of Popular Cultures).

Street art inspired by Aztec art along the Cuernavaca Railway Park Lineal.

A building painted in different colours. On any given street in Mexico City it is not uncommon to come across brightly coloured buildings like this one.

A trio of street tacos with accompaniments and hot sauces!

Enjoying a torta (Mexican sandwich) on the steps leading to Museo Nacional de Antropología (National Museum of Anthropology) made by a street vendor in Parque Museo Tamayo (Tamayo Museum Park).